7 February 2025: Donald Trump is threatening to raise tariffs for many countries, as a bargaining tool. The problem is that the country has become increasingly embedded in global supply chains and the trade balance has moved deeper into deficit. China has benefitted and has been taking a greater share of world trade. While US hawks might wish to disentangle from global trade, economic forces are pushing in the other direction. For base metals, the US is heavily reliant on imports of aluminium, copper, tin and zinc. There is little chance of this changing any time soon.

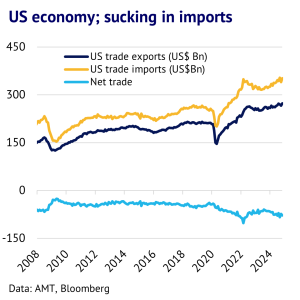

US has become increasingly reliant on imports. One of the stated aims of Donald Trump is to boost domestic manufacturing and reduce the countries “worrying” dependence on foreign goods and services. Looking at the US trade balance over the past 15 years there seems, at first glance, to be some justification for this concern. US trade imports increased to US$352bn by November 2024, up from US$165bn in January 2009, while exports increased more modestly to US$273bn, from US$126bn in the same period. This meant that the trade balance reached a deficit of US$78bn in November 2024, up from a deficit of US$39bn in January 2009. Economists would argue that this does not matter, if the deficit is offset by other financial flows, but perceptions matter and there has certainly been a hollowing out of manufacturing in the US and loss of jobs. What seems in little doubt is that the US has become more entangled in the global trade system during this period, for better or worse.

China has been boosting its market share, making it vulnerable to a global trade war. While the US has become more reliant on imports, inevitably other countries are on the other side of the trade and have been lifting their exports. China has certainly been a key part of this. Looking at China’s share of world trade, this trended up from just 10% back in 2013 to above 15% by 2021 (using a 12-month rolling average). However, since then the trend has been broadly sideways.

However, US hawks might focus on China’s high-profile trade surplus which has soared, as the country’s exports grew faster than its imports. China had a trade balance of close to zero back in 2013, but this reached a surplus of US$992bn by December 2024. The problem is two-fold. Exports are super competitive on the world market (for manufactured products, including electric vehicles and solar panels), but domestic demand is also lacklustre, which means that economic growth is becoming unbalanced. The Chinese government is well aware of this and has been implementing a mass of measures to boost domestic demand, but with limited success so far. China is now far more vulnerable to a global trade war than it was when Trump took office for the first time back in 2017.

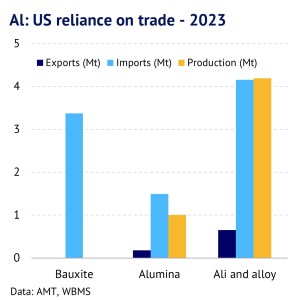

The US needs low-cost primary aluminium for downstream demand. Given this context, it is worthwhile examining how important trade is for the base metal markets and we start off looking at aluminium. While the US produces a lot of secondary aluminium (3.4mt in 2023), it is very dependent on imports of primary metal. According to CRU/WBMS figures, the US had a primary deficit of 3.9mt in 2023, and imports of both primary and secondary (aluminium and alloy) reached 4.1mt in the same year.

The US also imported significant amounts of bauxite, from places like Jamaica, and alumina, from places like Brazil, to feed its domestic smelters. The historical background was that US smelters were steadily mothballed over decades, due to high local power prices, and the gap was filled by countries, like Canada and the UAE, where cheap power provided a natural competitive advantage. While there might be a long-term ambition by the US to reduce imports, there is currently no spare domestic capacity to produce extra primary metal, leaving the US dependent on its overseas partners and, besides, there is no economic logic for unravelling the current aluminium supply chain.

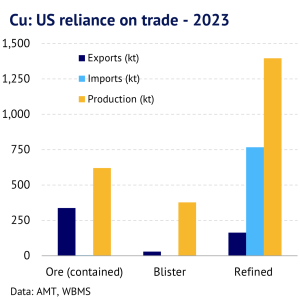

Chile is a key supplier for copper and domestic production is more significant. Looking at copper, there is less reliance on other countries, but trade is still important. US refined copper output was 1.4mt in 2023 and imports were 767t, most of which came from Chile. The US does also have significant amounts of local mining and output was 621kt (contained copper) in 2023, of which 338kt was sent overseas. For copper, there might be hopes of building a domestic copper supply chain, but the US is a notoriously difficult place to bring onstream new mining capacity, due to a long process of approval and environmental permitting. The giant Arizona project is a classic example, with its first mine plan submitted in 2013, but it has made little progress since then. This has meant that copper mining has instead grown in countries like the DRC, Mongolia and Peru, with the US offering unfulfilled potential for the future. Even if Donald Trump starts to approve new copper mines soon, it will probably take at least 5 years for them to come online.

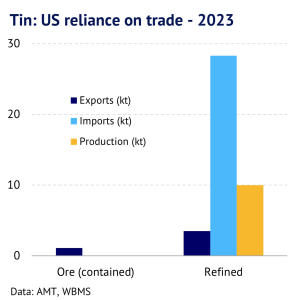

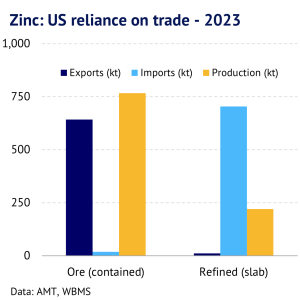

Tin and zinc trade patterns reveal areas of vulnerability. For tin and zinc, the US will also struggle to disengage from global trade any time soon. The country produces a small amount of secondary tin- around 10kt/y – but no primary metal. As a result of stronger downstream demand, the US imported a net 24kt of tin in 2023. Similarly, for zinc, domestic output fell short of local demand by a substantial 704kt, with Canada playing a key role in plugging this gap.

US caught in global trade trap of its own making. Global trade helps to benefit the US economy by providing goods from abroad more efficiently than they could be produced in the US. Also, US consumers get access to cheap goods being exported from China and other countries and US manufacturers can piggyback on low-cost sources of steel and aluminium from abroad. The current position has developed in response to comparative economic advantage and high environmental standards in the US, compared to other countries. Any attempt to unravel these supply chains within the metals industries will take decades.

Our previous research has found that for Donald Trump, business pragmatism normally triumphs over other considerations and this suggests that the US will remain deeply embedded in global supply chains for the foreseeable future, despite the potential for higher tariffs and damaged relationships with allies and enemies alike. The country has little choice.