What is Resource Nationalism?

Resource nationalism is the inclination of governments to seek greater control or revenue from natural resources in their territory. This is on the rise due to economic, nationalistic, and strategic factors amplified by the global pandemic. Punitive taxes, royalties, or other actions would likely hit mine project investment, but could also trigger top importing countries to invest more in alternative sources of metal such as recycling. This will be key as top economies seek security in the supply of metals critical for meeting long-term decarbonisation goals.

Governments seek to reap rewards of metals boom

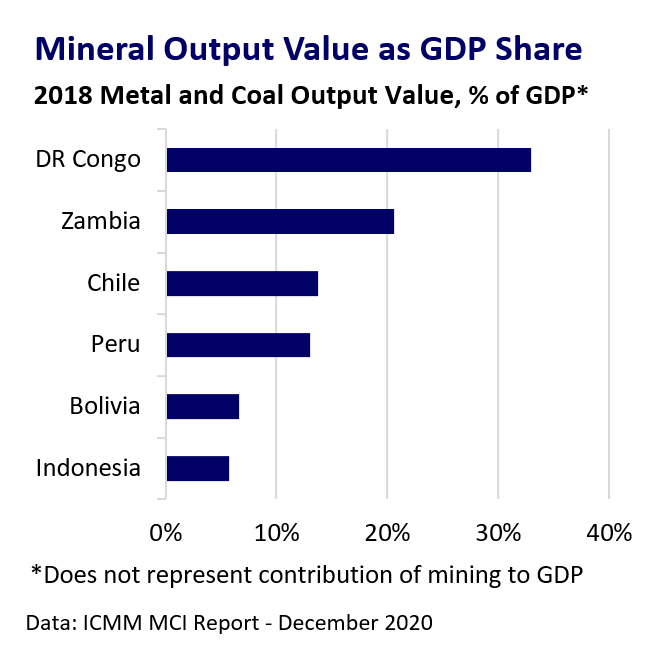

The economic drivers of renewed resource nationalism are clear. The global pandemic has dealt a heavy blow to the developing economies of key producers. Meanwhile, the price of metals produced in those countries, such as copper, has surged alongside mining company valuations. Mineral-rich countries are understandably seeking additional sources of revenue to revive their battered economies and finances after the pandemic; the mining industry is in the crosshairs. This motivation is most significant in countries where the mining industry represents a significant share of GDP. Countries in Latin America and Africa are notable in this regard.

Political change is also key

The popular rejection of globalisation in recent years has also fuelled calls for greater control over domestic natural resources. Chile and Peru are both under political pressure to address social unrest amid large wealth divides; Populist politicians have seized upon this discontent and national sense of entitlement to the spoils of domestic natural resource extraction. In South America, this represents a rejection of free trade principles and the neo-liberal politics of recent years.

Security of supply key to resource strategy

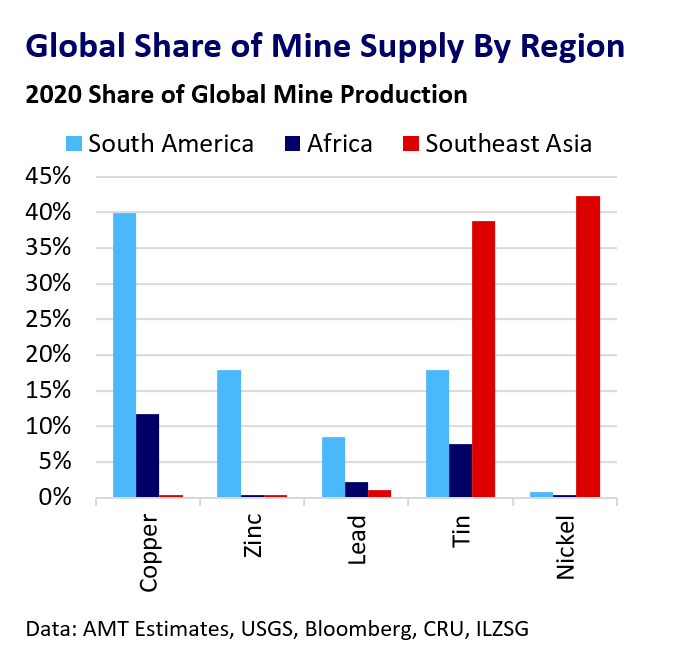

The US, Europe, and China have all made strong long-term decarbonisation commitments which will require big investments in infrastructure and technology like electric vehicles. This will inevitably fuel intense global competition to secure the metals required, further exacerbated by rising geopolitical tensions between China and western economies. This shifts power and strategic leverage to the mineral-rich countries controlling the supply of these critical metals. This will embolden them to extract a higher price both financially and geopolitically for international access to these resources.

Resource nationalism taking many forms

Politicians in Peru and DRC have called for increased taxes and royalties on mining. A bill to substantially raise taxes on Chilean mining companies also continues to make legislative progress. Zambia is in talks with producers to reform its mining tax rules. Governments may look beyond revenue to increased ownership and control. An early front-runner for Chile’s presidential election in November is calling for the state to have an ownership stake in all mining operations. Countries with mineral resources may also look to build up their value-added industries. Indonesia has achieved some success here in recent years through its ban on ore exports, most recently for nickel from 2020. The country also has ambitions to become a major electric vehicle battery supplier. Other resource-rich countries may look to take a similar approach. Scrap is emerging as a key resource as countries look to boost recycling rates and will likely become subject to stricter controls. The EU is currently reviewing rules on exports of waste as it looks to boost domestic recycling.

Implications

Efforts to extract more revenue from the mining sector will inevitably hit project investment and long-term confidence in the investment stability of the respective countries. The severity of this disruption will depend on how punitive the measures are. Barriers to trade in metals and minerals may erode free-market efficiencies and put upwards pressure on material costs on a global level. However, concerns about the security of supply may force major economies to boost investment or policy support for alternative sources of critical materials. This could include support for recycling, domestic mine projects, or higher-cost supply from regions with lower political risk.