What do global energy changes mean for metal prices?

Governments globally are ramping up efforts to reduce fossil fuel dependency. This is to meet ambitious decarbonisation goals and curb industrial pollution. China has curbed smelter production and capacity growth to meet energy targets. This has been price-supportive, most notably for aluminium. However, Europe’s developing energy crisis highlights how rapid decarbonisation poses risks to economic and social stability. Slower growth could weigh on metal consumption. This is despite clear demand opportunities from the green transition.

China Power Curbs

In recent months, China has applied increasing pressure on its Provinces to meet targets under its “dual-control” policy of reducing energy consumption and energy intensity.

Motivations include making progress on national decarbonisation commitments and tackling pollution. A looming power crisis from a shortage of coal and natural gas ahead of winter is also a key driver.

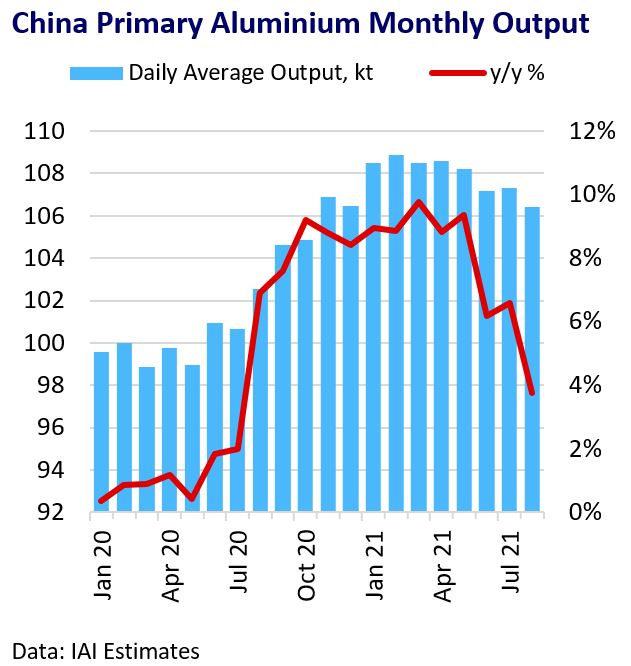

Provinces have turned to China’s industrial complex, including metal producers, to shoulder the burden of required cuts. Aluminium smelters have been hardest hit because of their significant electricity needs; domestic production has fallen notably since June.

Curbs could intensify as stronger winter demand strains the domestic energy market further. However, power restrictions on downstream industries could also weigh on economic growth and hit metals demand.

Europe’s Energy Crisis

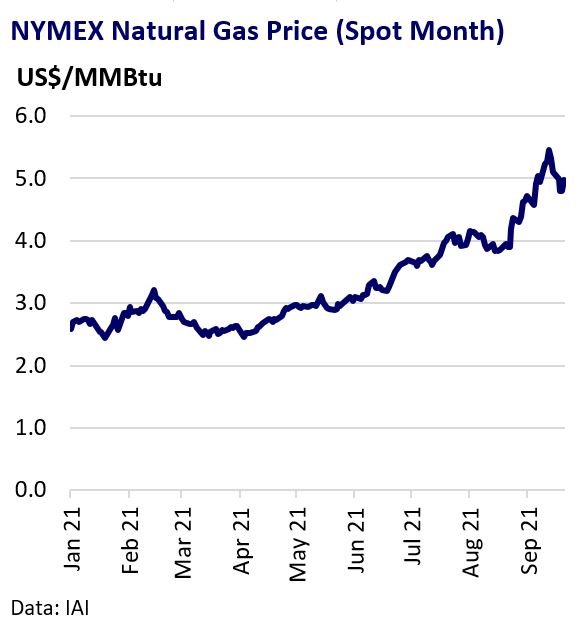

Europe also faces the threat of winter energy shortages. Natural gas prices soared in early September and mild weather has hit wind power generation.

While smelters with hedged power costs will have some protection, high electricity prices may deter idled capacity restarts. Citi estimates European aluminium producers may now be operating at costs of up to $2,900/t. A severe European energy shortage could lead to forced production curbs, although this is currently an unlikely scenario.

Like in China, both the broader industrial sector as well as individuals will feel the impact of higher power costs. This threatens to undermine economic confidence and growth. This may ultimately weigh on metals demand and counter supply losses.

Long-Term Implications

Current global energy shortages largely reflect strong demand and supply bottlenecks linked to the post-pandemic rebound. However, they highlight the dilemma policymaker’s face of how to drive rapid decarbonisation without threatening economic and social stability.

Europe is likely to phase out nuclear and coal-fired power stations in the years ahead and significantly boost renewables. Weather-related reliability issues for renewable sources are likely to translate into higher energy costs.

This may feed through to metals prices via higher production costs and curbs during periods of energy shortage. Yunnan Province in China experienced this issue earlier this year with a summer drought hitting hydropower generation.

It is worth reiterating that efforts to accelerate the share of renewable power generation will be positive for the metals necessary for that infrastructure, such as copper in power grids.

Supply growth may lag previous cycles as metal producers direct capital investment into low-carbon transformation projects and develop added-value products rather than capacity additions. The so-called “quality over quantity” approach.

Metals Most Affected

Aluminium finds itself most exposed to rising power costs and energy-related production curbs, although no metal’s production is immune. Copper is poised to benefit most from policy-led investments in renewable energy.

However, all metals are vulnerable to the possibility of weaker demand if higher global energy prices undermine consumer confidence, downstream industrial activity, and underlying economic growth.

Balancing the need to ensure the security of energy supply with decarbonisation goals will be an ongoing policy challenge, one to which metal markets will remain highly sensitive.